- Quick Links

- About Us

- Contact Us

- E-Paper

Search

Archives

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

© 2022 Foxiz News Network. Ruby Design Company. All Rights Reserved.

Notification Show More

LG Sinha felicitates CIPS Award Winners in Srinagar, calls for Innovation in Governance

Lieutenant Governor Manoj Sinha on Friday felicitated the winners of the Centre for Innovations in Public Systems (CIPS) Awards at a ceremony held in Srinagar. The CIPS awards recognize and…

Youth voices now roar in stadiums, not streets: LG Sinha

•Says no more hartals, only Khelo India calendars •OpensKhelo India Water Sports fest, champions J&K’s rise as sporting powerhouse •‘Since 2020, J&K hosts five editions of the Khelo India Winter…

Ephemeral fever detected in cattle, officials issue advisory

Srinagar, Aug 22: A new outbreak of Ephemeral Fever, also known as…

SVAMITVA flagship scheme : DC Kupwara distributes property cards

Kupwara, Aug 22: Deputy Commissioner (DC) Kupwara, Shrikant Balasaheb Suse today distributed…

DLSA Budgam conducts review of mentoring & monitoring committee of panel lawyers

Budgam, Aug 22: District Legal Services Authority (DLSA), Budgam, Friday convened a…

380 ltrs of lahan, 5 ltrs of illicit liquor, spirit recovered around Chadoora brick kilns

Budgam, Aug 22: The Central Kashmir Excise Range on Friday conducted a…

SMVDU celebrates World Entrepreneurs’ Day

Jammu, Aug 22: Shri Mata Vaishno Devi University (SMVDU) celebrated World Entrepreneurs’ Day with…

Mission YUVA : DC Ramban hands over 51 loan sanction letters to beneficiaries

Ramban, Aug 22: In a significant push towards fostering youth entrepreneurship and…

DC chairs DLIC meeting

Committee approves 238 cases under Mission YUVA

DC reviews Change of Land Use (CLU) cases

Poonch, Aug 22: Deputy Commissioner Poonch Ashok Kumar Sharma today chaired a…

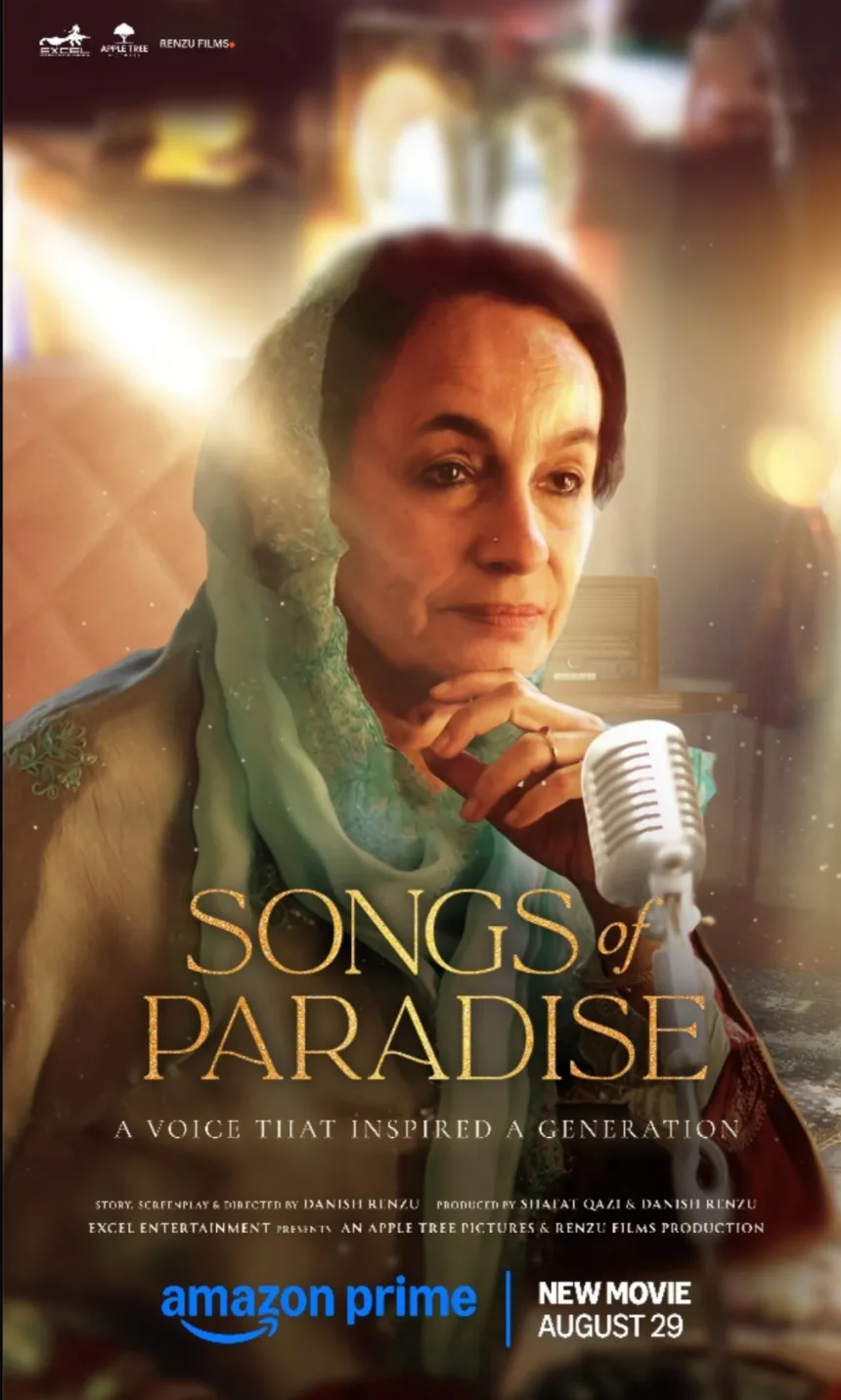

Prime video to stream ‘Songs of Paradise’ globally from August 29

Saba Azad, Soni Razdan lead Danish Renzu’s Songs of Paradise, inspired by Kashmiri icon Raj Begum

National Plant Health Initiative

In the 28th Prime Minister’s Science, Technology & Innovation Advisory Council (PM-STIAC) meeting on August 21, 2025 at National Agricultural…

Sports

BJP has earned people’s trust in Kashmir, says Ashok Koul

Srinagar, Aug 21: Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) Jammu & Kashmir General Secretary…

Weather

21°C

Srinagar

overcast clouds

21° _ 21°

81%

1 km/h

Sat

29 °C

Sun

21 °C

Mon

26 °C

Tue

27 °C

Wed

20 °C