Archives

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

Ramban cloudburst toll reaches 4; one missing, rescue on

Union Minister Dr Jitendra Singh, CM Omar assure help, direct officials to stay on high alert

JAMMU BATTLING DISASTER

• 11 killed as cloudburst, landslide devastate Reasi and Ramban villages • Seven members of a family buried alive in Reasi; four die in Ramban • CM Abdullah expresses grief,…

CBK busts fake MBBS admission racket, 4 arrested

Srinagar, Aug 30: The Economic Offences Wing of the Crime Branch Kashmir…

J&K cancels attachments of employees under NHM

Directs staff to report back by tomorrow

GMC Anantnag performs first-ever cochlear implant surgery

Offers new hope for children, aged 5 & 8, with severe hearing…

GMC Handwara leads J&K with highest DNB seat allocation for 2025

Srinagar, Aug 30: The National Board of Examinations in Medical Sciences (NBEMS)…

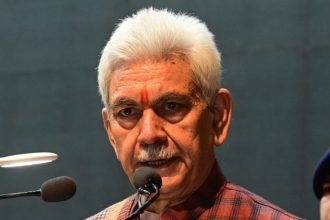

Swift efforts underway to restore flood-hit water supply infrastructure: Rana

Reviews restoration of water supply in ed Jammu

Loss of lives in Ramban, Reasi cloudburst : Rana, Javid Dar express grief

Jammu, Aug 30: Minister for Jal Shakti, Forest, Ecology & Environment and…

Poonch Police attach property of history-sheeter OGW active in PoJK

Poonch, Aug 30: In a significant legal action, Poonch Police today attached…

Javed Ranaa Chairs High-Level Meeting To Asses Restoration of Essential Services in Flood -Affected Areas of Jammu

Jal Shakti Minister Javed Ranaa today chaired a high-level review meeting with…

Kashmiri apples to reach Delhi markets faster as Northern Railways launches daily cargo train

Growers welcome, say ‘every day counts’

India-Japan Friendship

Global order is witnessing the reaffirmation of the old ties and friendships. The more things change the more they remain…

Sports

Hybrid model imposes limitations on elected govt, says NC’s Sagar

‘One-size-fits-all approach does not work in J&K’