The three major civilizations – Egyptian, Mesopotamian and Saraswati-Indus – of the world are the most ancient in nature. Although we find evidence of nature worship in all these three civilizations, yet recognizable differences exists. India stands out as a unique case where, despite many ancient civilizations losing touch with their original essence over time, Indian society has continued to uphold its 5,000-year-old traditions. The followers of these traditions today practice religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism.

In the Sanatan (eternal) tradition, there were various ways to worship the divine, one of which was the worship of the Linga. The Linga is considered the symbolic origin of the universe, as creation itself is believed to arise from the union of the Linga and the Yoni—hence its sacred status in Sanatan philosophy.

The oldest text of the Sanatan tradition, the Rigveda, contains descriptions of various deities, with prominent ones including Indra, Agni, Rudra, and Vishnu. Rudra, identified in the Rigveda as both creator and destroyer, is the early form of Lord Shiva. Numerous archaeological findings—some over 5,000 years old—attest to the worship of Rudra or Shiva in ancient times. Shiva has been venerated both in the form of the Linga and in anthropomorphic representations.

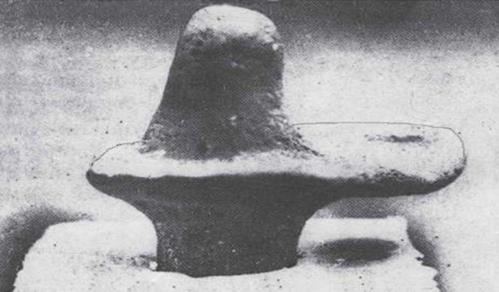

Evidence of Shiva worship is abundant in the ancient Saraswati-Indus civilization (also known as the Indus Valley Civilization). For instance, a terracotta Shivalinga was discovered at Kalibangan, and another was unearthed at Harappa, now in Pakistan. These artifacts are documented in publications of the Archaeological Survey of India and are displayed at the National Museum in New Delhi.

The human form of Shiva is also found in this civilization—most notably, a seal from Mohenjodaro depicting a yogi surrounded by animals, widely believed by archaeologists to be an early representation of Shiva as Pashupati (Lord of Animals). This demonstrates that Shiva worship was a part of life in that ancient society. The Rigveda also contains numerous references to Shiva. Additionally, symbols like Shiva’s trident (Trishul) appear on punch-marked coins from around 2400 years ago, indicating the widespread devotion to Shiva in ancient Indian society.

Even foreign rulers such as the Shakas and Huns, who invaded India, embraced Shiva worship. For example, coins issued by Hun ruler Vasudeva depict Shiva and his mount, Nandi. During the Gupta period (4th–5th century CE), Shiva worship became even more prominent, as evidenced by the production of numerous statues of the Shivalinga, Uma-Maheshwar, and Shiva-Parvati. Rock-cut caves dedicated to Shiva from this era can still be seen at Udayagiri in Vidisha.

Geographically, evidence of Shiva worship is widespread across India. Hindu kings of early medieval India built grand temples dedicated to Shiva, many of which are now UNESCO World Heritage Sites. The Brihadeeswarar Temple in Thanjavur (Tamil Nadu), the rock-carved Kailashnath Temple in Ellora (Maharashtra, 8th century), and the Kandariya Mahadev Temple in Khajuraho (Madhya Pradesh, 11th century) are all examples.

In the Kashmir Valley, Shivalingas dating back to the 1st century CE and later have been discovered, while in Tezpur (Assam), a 6th-century Shiva temple indicates the antiquity of Shiva worship in the northeast. This widespread presence illustrates that Shiva worship was a pan-Indian phenomenon and extended across South Asia.

Taken together, this evidence points to the continuous worship of Lord Shiva in India since the dawn of human civilization. Even today, during the holy month of Saavan, devotees following the Sanatan tradition engage in Shiva worship—just as their ancestors have been doing for the past 5,000 years.

(Author is Assistant professor, Department of History Shaheed Bhagat Singh College, University of Delhi)