The origin of human beings has always remained a fascinating subject regarding the cradle, ancestor and time of origin, our relationship with those who came before us. What makes us the present day humans and so on are some of the questions that strike in our minds? Svante Pääbo the Swedish Nobel Prize winner in Medicine in2022 had proved through his work that modern humans shared some of their genes with the ancient and now extinct Neanderthals. This meant early human had come into contact with these human-like species, the Neanderthals, and they interbred.

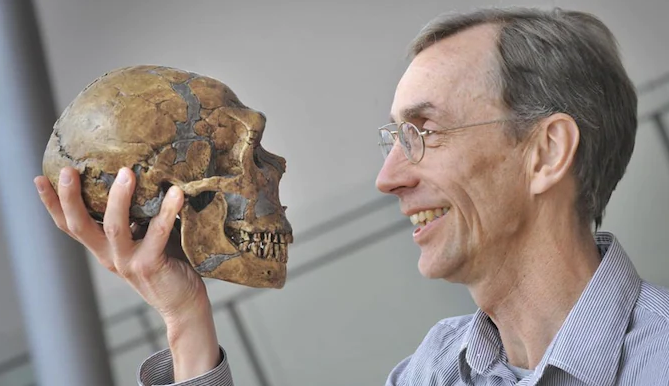

Prof Pääbo, Director of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig-Germany in 2010, published the genomes sequence of the Neanderthal, an extinct relative of present-day humans at that time nobody would have thought that for this work Pääbo will get Noble Prize. He went on to discover a previously unknown branch of the human family tree by extracting DNA from a 40,000-year-old finger bone found in a cave in Siberia. The new hominid was named Denisova after the location in which the bone was discovered. In his study mitochondrial DNA was sequenced to minimize the contamination and to get DNA as pure as possible.

These children of Homo sapiens —that Is the scientific name of humans— and Neanderthals had then integrated with the humans and the traces of the long-lost relationship is still retained in the form of common genes. The findings were revealed by the scientist in 2010, which had created sensation then. The Neanderthal genes were extracted by Pääbo from some fragments of bone samples in a remote cave in Siberia. But later on he had developed his methodology so well that now it is possible to discover these genetic structures without having to extract from bones. His work has established that these can be extracted from even the dust from the caves where these lost tribes had lived. Even the genetic structures of extinct mammals and other animals could be extracted thus.

Subsequently, Pääbo’s discovery and seminal work had founded what has come to be known as “paleogenomics”, that is, study of the genetic structure and composition of populations long extinct. This is a new science and established discipline now. The work is no less fascinating than detective stories, but of singular importance for the overall story of the evolution of modern human beings in their interactions with the environment. The Neanderthals had gone extinct some 40,000 years back.

Homo sapiens first appeared in Africa approximately 300,000 years ago, while closest known relatives, Neanderthals, developed outside Africa and populated Europe and Western Asia from around 400,000 years until 30,000 years ago. Pääbo found that most present-day humans have one per cent to four percent of their DNA common with Neanderthals, meaning Neanderthals and Homo sapiens must have encountered one another and had children before Neanderthals went extinct around 40,000 years ago. The interbreeding of Neanderthals with the Homo sapiens has been strongly doubted by many scientists for many years. It is now believed that Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa 70,000 years ago and gene transfer took place between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens.This finding not only traces the evolution and gene flow but has great importance in physiology and also to know things like how our immune system reacts to infections.

The findings of common DNAs between humans and Neanderthals were the first building block for the new science of paleogeneology of humans. The genome he sequenced showed an entirely new kind of extinct human, called Denisovans after the name of the cave. These populations had a distinct gene named EPAS1 are the marker of the Neanderthal traces in humans. By comparing Denisovan DNA with the genetic records of modern humans, Pääbo then showed that some populations in Asia and Melanesia inherited up to six percent of their DNA from this enigmatic ancient human. This is said to be of medical importance today.

It has been found that those populations having higher Neanderthal genes in their body are more adept at surviving and acclimatizing in high altitude areas. Among them are the Tibetans. Maybe, the Nepali Gorkhas also share this feature with their Tibetan brothers. After all, they share the same kind of their habitats with the Tibetans and could have followed the same mighty paths before separating out in their distinct new habitats. Pääbo’s early love was to study Egyptian mummies. He had studied the ancient mummies at night secretly to extract and find their genetic sequences. With the advent of new technologies the picture of human evolution may become clearer in near future.

(Dr. Aijaz Hassan Ganie Department of Botany, University of Kashmir)