Dr. ASRAR QURAISHI

Islamic medicine refers to the range of health-promoting beliefs common to and actions taken in Muslim societies, whether by Muslims or others. As with other traditional medical systems, Muslim medicine was composed of several subsystems, each involving a unique etiology and practice and each enjoying a different legitimacy. These subsystems were not independent of each other and none enjoyed complete hegemony. In the Muslim context this means that humoralism, folklore, and prophetic medicines were all present in the medical therapeutic scene.

Theories Composing Muslim Medicine

Popular medicine was sanctioned by custom, a wide consensus from below, not by any religious, judicial, or scientific authority. This medical folklore in itself took many forms and was the outcome of diverse pre-Muslim cultural traditions (such as those of Arabs, Greeks, Persians, and Berbers) and differing ecological environments with their distinctive medical problems as well as flora and fauna from which medication was prepared.

By contrast, what Muslims call Prophetic Medicine (al-Tibb al-Nabawi) does not rely on custom. Instead it originated from (and therefore is sanctioned by) the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). These sayings, in which the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) gave his opinions on medical practices, constituted the basis for a distinctive medical system from the ninth century onward. In general, the field of Prophetic medicine engaged many of the most renowned scholars of their time for example, the Egyptian Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti.

Mechanical medicine, based on the humoralism inherited from Greek antiquity, constitutes another tradition. This medicine is based on the well-known idea of four elements: a physical and philosophical Metatheory according to which everything in nature is a mixture of fire, earth, air, and water. Each element embodies two of the four qualities of hot, cold, dry, and moist.

The human body was understood to correspond with this model, because it is a microcosmos of nature. The body consists therefore of four humors, or fluids, the physiological blocks of the body: blood (air), phlegm (water), black bile (earth), and yellow bile (fire). In case of illness, which is a state of imbalance in the body, it was up to the humoralist physician to diagnose which of the four humors was in excess or deficient. The physician then proceeded to recommend a course of treatment, usually by diet, to correct or counterbalance the offending humor. Excess in black bile, for example, known to be cold and dry, necessitated adding warmth and moisture artificially. This tradition asserted its legitimacy by drawing on scientific treatises of the sages of antiquity, as mediated through the intellectual and literary discourses of famous Muslim medical figures.

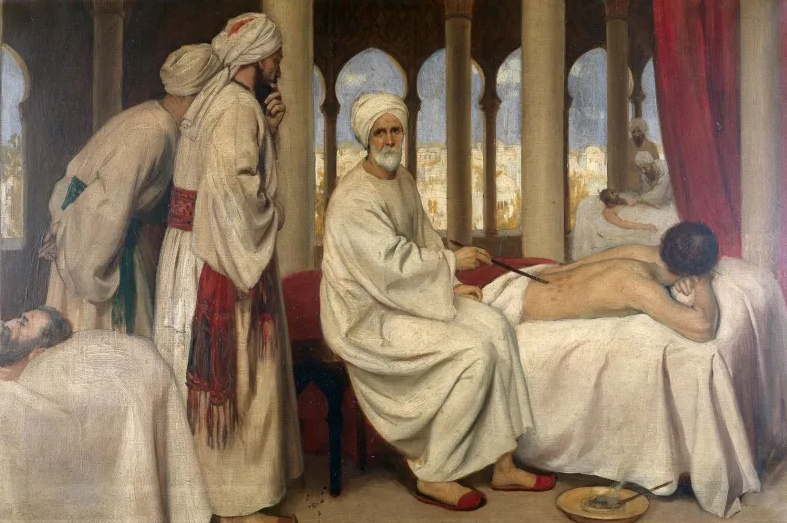

Hospitals

One of the unique features of Muslim medicine was the use and development of hospitals (bimarsitans or dar al-shifas). Hospitals were founded in most major Muslim cities, starting in Baghdad, the capital of the Muslim empire, in the ninth century, and reached an especially high standard during Mamluk and Ottoman periods (from the thirteenth century). Muslim hospitals were urban charitable institutions funded by endowments (waqfs) that offered free treatment to the sick by an expert medical staff. In contrast to their European counterparts, Muslim hospitals were ‘true’ hospitals in that they were designed to offer the sick expert medical treatment by professionals, whereas many pre modern European hospitals, mainly in the Medieval Latin West, usually restricted themselves to spiritual aid and substance to exhausted and convalescent people.

Ages of Translations

Muslim medicine has always been in contact with other medical systems through translations of medical treatises. The translation movement has worked in both directions; that is, both to and from Muslim languages. Muslim Galenic medicine owed much of its origin to a massive move to translate from Greek to Arabic in the ninth century. This was part of the general introduction of Hellenic culture and science into the Muslim world.

Most of the translations were done via mediator languages, mostly Syriac and to some extent Persian. Translators, many of whom were Christians (such as the famous HusaynibnIshaq), enjoyed caliphal patronage. Al-Ma’mun (reigned 813–833) should be given special mention for sponsoring the great library of Baghdad, Bayt al-Hikma(literally, “House of Wisdom”), which was the center of intellectual activity at the time. Although we associate the Age of Translation with Hellenic medicine, during the ninth century traditional Indian medicine (Ayurveda) was translated into Arabic as well, either directly from Sanskrit or by way of Persian. In the long run, however, it was Hellenic medicine that became dominant in the caliphal court.

Muslim doctors were the custodians of Hellenic medicine, which they expanded, corrected, systemized, and summarized (for example, in the fields of pharmacology, ophthalmology, pathology, and many others). In anatomy, for example, Ibn al-Nafis is credited with describing the circulation of blood in the lungs for the first time. He formulated this description through logical deduction rather than clinical observation. Many Muslim medical texts were translated into European languages during the later Middle Ages. Thus many Muslim physicians became known to Europe, as well as otherwise “lost” texts from antiquity. Figures like Abu BakrMuham- mad ibnZakariya al-Razi,Abu Qasim al-Zahrawi, and IbnSina were famous in Europe by the Latinized form of their names (Rhazes, Albucasis, and Avi-cenna, respectively), and their treatises became standard medical texts well into the eighteenth century.

In the early modern period another move to translate medical texts occurred, again from European to Muslim languages. This time non-humoral concepts were introduced to Muslim medicine. A prime example of a physician who applied the concepts of European medicine is SalihibnSallum, from Aleppo,the head physician of the Ottoman Empire, who was influenced by Paracelsus, the German-speaking physician who was the first to treat patients with chemical rather than botanic or natural medications. IbnSallum’s work in Arabic was soon translated into Ottoman Turkish. Translation of European texts accelerated in the following centuries, especially during the nineteenth century, when many European texts were translated into Muslim languages as part of the move from traditional medicine to Western biomedicine.

Changes from the Nineteenth Century Onward

Beginning with the late eighteenth century, major political and socioeconomic transformations have occurred in the Muslim world that profoundly changed medicine and public health. European medicine was introduced on a much larger scale in various ways. Students were sent to universities in Europe to learn medicine. In addition, medical schools were shaped according to the Western model, at which European professors taught European medicine in French, were founded in all major capitals of the Middle East during the first half of the nineteenth century. The first was established in 1827 near Cairo, followed shortly by a military medical school in Istanbul. The third, another military medical school, was included in a polytechnic school founded in Tehran in 1850–1851.

Despite the profound Westernization of medical theory and the medical establishment in the Muslim world, traditional Muslim medicine is still being practiced. It is not found in the state-run hospitals or in universities, but it is present at the popular level. Religious circles promote Prophetic Medicine, and in recent years many traditional texts have been reprinted and Internet websites devoted to this subject have been set up.

(Author is a Historian and columnist)