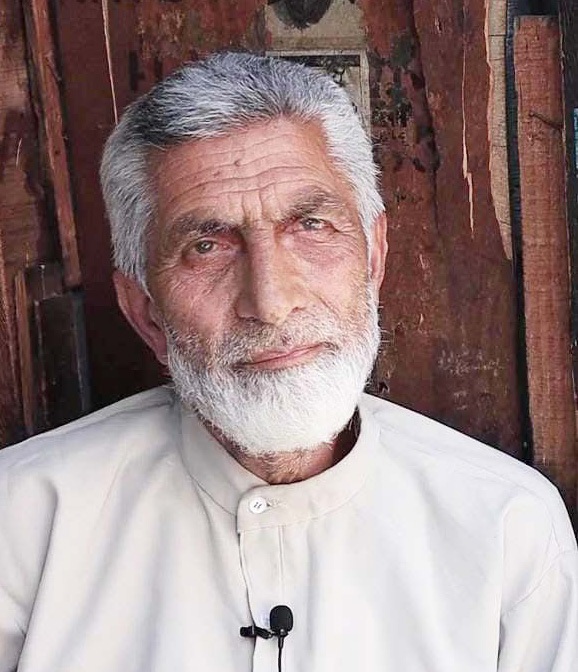

In the tangled tapestry of Kashmir’s history, where culture breathes through craft and tradition hums through narrow alleys, the story of Mohammad Yousf emerges not merely as a tale of survival but as a quiet rebellion against forgetting. Nestled in the bustling lanes of Maharaj Gunj, one of Srinagar’s oldest market districts, Yousf’s small tailoring shop is a sanctuary of memory—where threads don’t just bind fabric but hold together the fragments of a vanishing heritage.

At 50, Mohammad Yousf is not merely a tailor; he is a guardian of a cultural lineage that now teeters on the edge of extinction. For more than forty years, Yousf has devoted his life to stitching skull caps and traditional Kashmiri innerwear known locally as Baend. In a world racing toward synthetic efficiency and global fashion, Yousf’s dedication to a craft most now regard as obsolete is both poignant and powerful.

“I’ve been making skull caps for the last 40 years,” he says, seated beside his timeworn sewing machine that hums like a companion in solitude. “But with changing times and less demand, I had to shift to stitching Baend, which are still used by the elderly.” His words echo the quiet resignation of an artisan witnessing the slow erosion of relevance. And yet, behind his eyes lies an unmistakable flicker of pride—of someone who has not given up.

The Baend, once a ubiquitous garment in Kashmiri households, carried a value far beyond its physical form. Made of cotton and tailored for comfort, it was also cleverly functional. “People used to sew small pockets in them to keep whatever little money they had,” Yousf recalls. “It was a necessity during tough economic times.” In a place marked by political turmoil and financial hardship, these garments were symbols of resilience—humble yet resourceful, much like the people who wore them.

Yousf’s story is interwoven with the rhythms of a changing Kashmir. In his early days, cotton was a precious commodity, and he and his wife had to scrape by with limited means. “Cotton was expensive then, and yet we managed to cradle our family within that limited income,” he says, his tone devoid of bitterness. His wife spun cotton yarn at home, each spindle a quiet act of love and partnership. Together, they embroidered a life of modesty and dignity, guided not by prosperity but by purpose.

What makes Yousf’s journey extraordinary is not just the duration of his labor but the spirit behind it. “I worked hard for 40 years. I still remember working till midnight just to make ends meet. But I’m thankful to Almighty Allah for everything,” he shares. His gratitude is striking, especially in an era when labor is often measured only in profit and productivity. For Yousf, the work was never just about livelihood—it was about upholding a tradition, about honoring the craft handed down through generations, even when no one else seemed to care.

Today, as modern clothing supplants age-old garments and machine-made fabric floods the markets, artisans like Yousf stand as silent sentinels of a culture that refuses to be erased. His clientele may have dwindled to a handful of elderly loyalists, but the stitches he sews carry the weight of history. Every Baend he makes is a whisper from the past, a reminder that identity is woven not in monuments but in daily rituals, in the quiet devotion to what came before.

In the globalized race to redefine culture, there is an urgent need to pause and recognize the quiet laborers of heritage—people like Mohammad Yousf, who, in their steadfast routine, resist the homogenizing currents of modernity. His story is not just one of economic endurance but of cultural resistance. In every thread he stitches lies an act of remembrance, a gentle refusal to let Kashmir’s sartorial memory be consigned to museums or footnotes.

As the summer sun casts long shadows over the wooden facades of Maharaj Gunj, Yousf’s sewing machine continues to purr, perhaps a little slower, perhaps a little softer, but it sings still. In that unhurried melody lives a century of Kashmiri resilience, faith, and craftsmanship—stitched not just into cotton, but into the soul of a place that remembers even as it changes.