Long before smartphones lit up screens and social media shrunk attention spans, a silent revolution in ink and intellect stirred in the alleys of Maharaj Gunj. At its centre stood Ghulam Muhammad Noor Muhammad Tajiran-e-Kutab—a name etched in the literary and cultural memory of Kashmir.

Founded during the reign of Maharaja Pratap Singh, when printed books were a rarity in the Valley and most came from Lahore or Lucknow, Noor Muhammad’s shop was Kashmir’s first whisper of self-reliance in publishing.

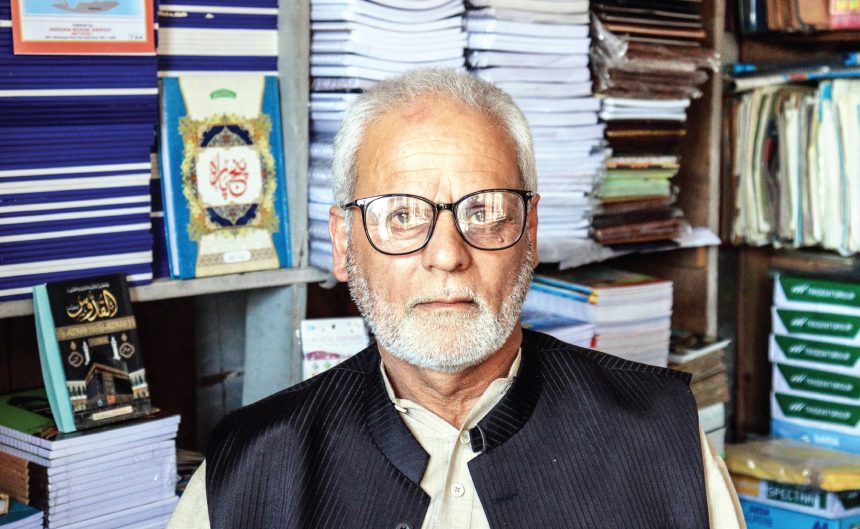

“There were no printing presses in Kashmir back then,” recalls Muhammad Iqbal Kitab, a third-generation descendant of the founder. “Noor Muhammad changed that.”

By the 1930s and 1940s, this modest bookshop had transformed into a full-fledged printing press, fuelling Kashmir’s intellectual and cultural awakening. In an age when literacy was just beginning to take root in the Valley, Noor Muhammad’s press became a bridge between tradition and transformation.

“Every newspaper in Kashmir was once printed from our house,” says Kitab. “We weren’t just selling books—we were preserving identity and nurturing resistance through the written word.” It wasn’t just about printing ink on paper—it was about giving voice to ideas that shaped Kashmiri consciousness. From political tracts to poetry compilations, from textbooks to spiritual scriptures, the press carved a niche that no other establishment of its time could match.

When Maharaja Hari Singh introduced mandatory education in 1928, many viewed it as just another administrative reform. But Noor Muhammad saw something deeper. “He composed a heartfelt poem celebrating the announcement,” Kitab says. “For him, education was liberation, not just policy. He understood that knowledge was the first step toward freedom.”

His poetry—handwritten, printed, and distributed—wasn’t just a reaction to a policy change. It was a celebration of enlightenment, urging the masses to embrace books and learning in a language they understood. As their footprint grew, the family opened more shops in key cultural hubs—most notably Lal Chowk. These were not just retail spaces; they became meeting grounds for Kashmir’s literary elite. “Our shelves were visited by legends—Mehjoor, Abdul Ahad Azad, Dina Nath Nadim, Ahad Zargar, Samad Mir,” Kitab recalls. “Even Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Hafiz Jalandhari walked in. It was a place where verses met vision.” Tea was served, manuscripts were debated, verses recited, and books were bartered and gifted. Noor Muhammad’s space wasn’t merely a commercial venture—it was Kashmir’s informal academy, its think tank, its printing parliament.

One of the press’s most profound contributions was linguistics. At a time when religious texts were confined to Sanskrit, Arabic, or Persian, Noor Muhammad’s press was the first to publish the Quran and Ramayan in the Kashmiri language. “We wanted to bring sacred scripture and heritage closer to the people,” says Kitab. “Language should never be a barrier to spiritual understanding.”

They also published Ram Leela and Krishen Leela, ensuring that Hindu epics found a home in Kashmir’s linguistic landscape. In doing so, Noor Muhammad was not just a publisher—he was a cultural bridge-builder. Equally valuable was his effort to collect, transcribe, and print the works of Kashmir’s mystic saints—Sheikh-ul-Alam (RA), Lal Ded, Wahab Khar, Waza Mehmood, and Ahad Zargar. Their verses, often orally passed down, risked being lost to time. “He feared their voices would fade,” says Kitab. “So he turned his press into a time capsule.” Their poems, imbued with themes of unity, compassion, and transcendence, were published in simple formats, sold affordably, and distributed across villages. The Noor Muhammad press ensured that mysticism was not the preserve of scholars—it belonged to the people. With the advent of the internet and digital devices, however, the story took a different turn. Printing presses began falling silent, and books started gathering dust.

“The ritual of touching, reading, and gifting books is fading fast,” Kitab laments. “We’ve moved from pages to pixels.” He speaks of generations that once saved pocket money to buy books of poetry, who now scroll endlessly but absorb little. “People used to carry books in their pockets. Now they carry screens. We are losing not just readers, but the very essence of reflection.”

Despite the tide of technology, Noor Muhammad’s story still resonates. Tucked into the memory lanes of Srinagar, his contribution is a testament to what Kashmiri resilience has always stood for—preserving identity through the power of language, faith and ink. “That shop in Maharaj Gunj wasn’t just a business,” Kitab reflects. “It was sacred ground. It kept the flame of Kashmiri thought alive.”

Today, the story of Ghulam Muhammad Noor Muhammad Tajiran-e-Kutab is more than a forgotten footnote—it is a reminder. “That we once had a press that printed sacred scripture and revolutionary poetry,” Kitab concludes. “A press that believed knowledge could unite, heal and empower Kashmir.”