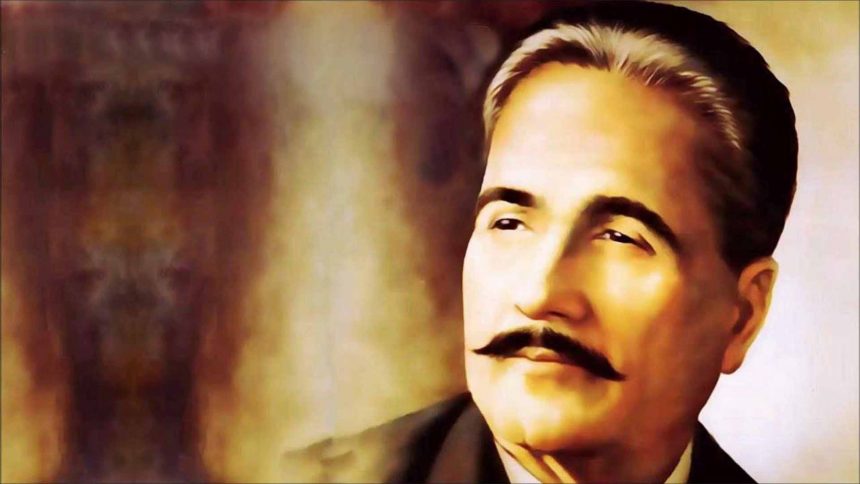

Born in the Punjab in 1877, Muhammad Iqbal was thoroughly educated in both Muslim and Western traditions. He was a descendent of an aristocratic Brahmin (Sapru) family of Kashmiri origin who had embraced Islam some three centuries ago. Upon graduating from the Govt. College in Lahore in 1889, he remained a lecturer there for six years. From 1905 to 1908 he studied philosophy at Cambridge and Munich, also qualifying for law. After he returned to Lahore, he earned his modest living as a lawyer, devoting his spare time to his poetry.

Iqbal’s poetry is full of religious emotionalism, based on reason, which characterized the Muslim thought of this period. He wrote his poems both in Urdu and Persian, particularly in Persian because he sought to address his appeal to the entire Muslim world. He, however, succeeded in avoiding the pitfalls of pathetic fantasy, eroticism and over sentimentality, all too characteristic of even the most celebrated classical poets of Persian language. His poetry demonstrates beyond doubt, his keen understanding of the proper role of the artist in Islam.

Although he addressed his message directly to the Muslim nation, but what he conveyed was a matter of universal import. The broad universal religious outlook that he presented in his poetry as well as philosophical writing was meant for the whole humanity. He made an attempt to revive the entire Muslim world by a liberal and dynamic view of Islam. He deplored the geographical and racial divisions of humanity and attacked bitterly the jingoistic nationalism that had resulted in the suicide of a whole civilization.

Among his Persian poems, ‘The Secrets of Self’ and ‘The Mysteries of Selflessness’ are the most thought-provoking. In these two poems, he presents a story of the self which is plainly a reaction against the doctrine of self-annihilation developed by Muslim mystics under the influence of non-Muslim religious (mystic) thought. He argued from the Qur’an and early Muslim history that Islam is a doctrine of self-assertion which teaches man to work for the attainment of worldly power and to attempt the conquest of self and the non-self.

The first phase of Iqbal’s poetry, in which he is found to be a free-lance poet expressing everything freely and advocating territorial nationalism based on the love for the motherland to do away with the British rule, ended when he went to Europe for the study of Western philosophy and culture. Many a student during this period returned from Europe either completely denationalized becoming by a blind imitation a travesty of a Westerner, of fired with the idea of territorial nationalism. They came back Westernized in their whole mode of liking. Overwhelmed by the achievements of the West in science and technology, they belittled even the good aspects of their own cultural heritage. They desired their community to become dynamic and progressive, and the only way they considered to be effective was to adopt Western attitudes uncritically.

Iqbal was one of those few observers of Western civilization who saw also the seamy side of it. It was ruthlessly competitive society split up into antagonistic nations bent upon exploiting not only their own working classes, but also making all unorganized, technically backward people of Asia and Africa victims of economic imperialism. Iqbal was convinced that Europe was heading towards a catastrophe, because of its purely materialistic outlook divorced from ethical and spiritual values. So he became an enemy of Western economic and political imperialism and colonialism and a bitter critic of Western nationalism and naturalism, which, overwhelmed by the achievement of physical science, has lost faith in the reality of the spirit.

Iqbal’s poetry is filled with such instances which bring out the fact that Western civilization is based on the pollution of mind and spirit veiled by the sparkling of its development. He says in Zarb-iKalim:

Fasad-i qalb-o nazar hai farang ki tahzib;

Ki ruh iss madniyat ki rah sakina ‘afif!

Rahay na ruh mayn pakizgi tou hai napayd;

Zamir pak wa khayal-I buland wa zok-i latif!

This divorcing of the spirit led to the darkening and dissatisfaction of life which this civilization reflects. This materialistic and mechanical dye in which this civilization has dyed itself in has thrown it away from the mercy of God.

He says in the same composition:

Yah ‘aysh-i farawan yah hakumat yah tijarat;

Dil sina-i nur mayn mahrum-I tasalli!

Tarik hai afrang mashinun kay dhuwayn mayn;

yah wadi-i ayman nahin shayan-i tajalli!

This Graeco-Christian civilization, although youthful and energetic vis-à-vis its age and achievements, is actually on its deathbed insofar as its erroneous traits are concerned and it can be easily anticipated that the Jews would become heirs to it. Iqbal laments:

Hai niza‘ ki halat mayn yah tahzib-i jawan marg;

Shayad hun Kalisah kay yahudi mutawalli!

However, it seems that this civilization would not die a natural death. It would, in all probability, commit suicide instead. Iqbal continues:

Tumhari tahzib apnay khanjar say aap hi khudkashi karaygi;

Jo shakh-i nazuk pai aashiyana banayga napay’i darhoga!

This civilization has rendered all its endeavors of unfolding the secrets of nature and the benefits thereof to naught by its negligence of and indifference to the ethical legacy of humankind. Iqbal says:

Who fikr-i gustakh jis nay kiyahai ‘uryan fitrat ki taqatun ko;

Isi ki baitab bijliyun say khatar mayn hai isska aashiyana!

Iqbal is making an anticipation that a new world order is emerging in that world which has been rendered into a gambling-chamber by the custodians of this civilization themselves. He says:

Jahan-i nau horaha hai paida who ‘alam-i pir mar raha hai;

Jisay firangi maqamirun nay banaya hai qumar-khana!

On another occasion, Iqbal says that the lustre of this civilization is just an illusion. Actually, it is brute in nature and dark at its core. He made this point in these words:

Yah ‘ilm yah hikmat yah tadabbur yah hakumat;

Pitay hain lahu daitay hain ta‘lim-I masawat!

Although Iqbal had fully acquainted himself with the wisdom of the Occident, he chooses for himself certain ideas and then adopts some of them critically and rejects some outright. The worship of the State to which Hegel had given a philosophical grounding, was producing thinkers like Nietzsche and Trotsky for whom the power of the super-man or super-nation had become the ultimate good of individuals as well as nations. Iqbal was disillusioned by studying this all and he stood for the fusion of the material and spiritual and criticized Nietzsche because his super-man accepted no moral or spiritual bounds to his power.

The same union of the spiritual and temporal characterizes Iqbal’s concept of the State and, on the same ground, he opposed the concept of nationalism and the secular philosophy of the State associated with it. He thus repudiates nationalism –the very basis of the Western philosophy– for nationalism is earth-rooted and thus opposed to the principle of movement which is one of the fundamentals of Islamic teaching. The migration of the Prophet Muhammad (SA‘AS), from Makkah to Madinah, typifies to Iqbal the dynamic nature of Islam, with its freedom from geographical and racial limitations.

(Author is Sr. Assistant Professor, Islamic Studies at GDC Sogam, Lolab. Feedback: [email protected])