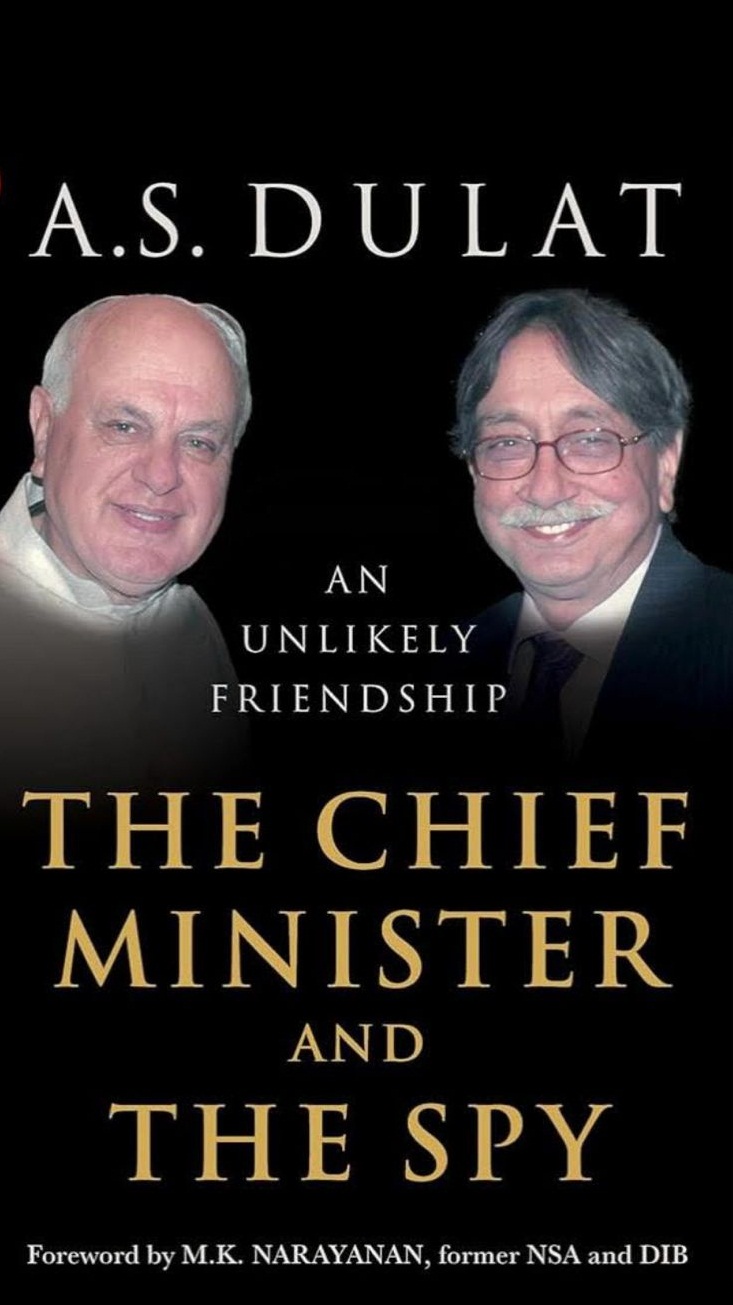

BOOK REVIEW

There are books that are less about politics and more about politicians as people. Such books are shaped more by personal relationships than political events. In that sense, the book titled ‘The Chief Minister and the Spy’ by A.S. Dulat is less of a memoir and more of a personal tribute to one man: Dr. Farooq Abdullah, the long-time political leader of J&K.

The book’s tone is warm, familiar, and mostly nostalgic. Dulat shares private moments with Farooq across decades. That closeness forms the spine of the book, giving it heart but limiting its scope.

That explains why there are several moments in the book where a more critical eye might have been helpful. For instance, Farooq’s decision to go abroad in 1990, just as the Valley was slipping into militancy, is briefly mentioned but not seriously examined. This leaves its political or moral implications unanswered.

That avoidance became especially visible when the book’s most controversial claim made headlines. Dulat writes that Farooq, despite publicly opposing the abrogation of Article 370 in 2019, told him privately: “We would have helped. Why were we not taken into confidence?” This single line created a political storm. Farooq immediately denied ever saying such a thing, called the book “full of mistakes,” and his party, the National Conference, distanced itself from the claim. Even former Chief Justice T.S. Thakur dropped out of the book launch.

Dulat responded to such criticism with a mix of humor and frustration. “English is a difficult language,” he said, suggesting the comment had been taken out of context. But the controversy revealed something deeper about the book: that it relies heavily on private conversations and personal trust. When that trust breaks down, the whole narrative can unravel.

The author reduces the repercussions of such events to memories between friends rather than as parts of a larger historical or political puzzle.

However, where Dulat succeeds is when capturing the emotional weight of certain moments. His account of visiting Farooq during his house arrest in 2019 is especially moving. Farooq is shown not as a confident leader, but as a hurt and confused man. “What have we done to deserve this?” he asks. Dulat doesn’t answer the question, but the description of the scene lingers in the reader’s mind. These parts of the book show the personal cost of political decisions in a way that formal histories often miss.

Dulat reveals that the government of Narashimha Rao was willing to discuss any kind of political arrangement with Kashmir; “any quantum of Azadi.” When Daulat conveyed this to Farooq, he responded by saying: “Kehne se kya hotahai?

“Uper Hawa mein batein karne se kya fayada.” (What do words mean? What is the point of merely saying something?) The book informs that Farooq was keen on autonomy without expanding what it really meant.

One expected Dulat, who had worked both in Srinagar and later as head of RAW and in Prime Minister Vajpayee’s office, to examine the menace of terrorism in a more structured and meaningful manner rather than see everything through the charisma of Farooq.

It is worth recalling what the former Advisor to the Governor, Ved Marwah (retd. IPS), wrote in his well-acclaimed book ‘Uncivil Wars: Pathology of Terrorism in India’: “More than the 1987 rigging in elections, it was the lack of coordinated action between the governments in Srinagar and New Delhi that was responsible for the spread of terrorism in Kashmir… Time and again opportunities came for controlling terrorism, but each time the opportunity was thrown away by short-sighted policies and actions.”

What emerges from reading the book is that Farooq seemed more interested in being Chief Minister than in governing the state. Referring to the idea of enduring jail time for a political cause, Farooq candidly stated:

“If you have in mind someone who ends up in jail, you can count me out. I am the last person to like being jailed. I like to play golf. What am I going to do in jail? You may suggest that I read books to while away time, but I would not like to do that because reading puts pressure on my eyes.”

Dulat takes this forward and compares Farooq to his father, Sheikh Abdullah. Sheikh openly challenged Delhi, spent years in jail, and became a towering figure in Kashmir’s political history. Farooq, in contrast, chose to work with the central government, staying within the system even when it disappointed him. Dulat suggests that this approach was wiser in the long run. “Farooq was in politics to work with Delhi, not against it,” Daulat argues.

But again, the analysis doesn’t go very deep. Was Farooq’s pragmatism a strength, or did it weaken Kashmir’s political voice? The book doesn’t addresses this.

If it is this divergence-confrontation versus collaboration-that leads Dulat to call Farooq a taller leader than Sheikh Abdullah, then it is a flawed conclusion. Senior Supreme Court lawyer, Ashok Bhan, has accurately commented elsewhere that three actors helped secure Kashmir for India: Nehru, Sheikh, and the Indian army. Therefore, to compare Sheikh with his Farooq on equal terms is not grounded in historical fact.

However, the author should have examined the factors that have led to the huge dip in the appeal and charisma of the entire Sheikh family- as became evident when militancy erupted in 1989–90. The militants gave a call to observe 8 September, Abdullah’s death anniversary, as a day of deliverance—yome-e-nijat. A near-total bandh was observed in the Valley, and effigies of Sheikh were burnt at various places.

The fact is that Dulat does not question the political inconsistencies as seen in Farooq over the decades. He never fully explores whether his leadership has helped or harmed Kashmir during crucial periods.

Incidentally, there were three leaders who never found favour with Farooq Abdullah: Jagmohan, whose appointment as Governor in 1991 he strongly opposed; Mufti Mohammad Sayeed, whom he criticized for yielding to militants’ demands during the Rubiya Sayeed kidnapping episode; and Safiuddin Soz, whom he regarded as unreliable.

The most entertaining and absorbing chapter relates to the father-son equation. Daulat is at his best when he engages in comparing the two in their policies, their outlook etc. “Farooq has always been the quintessential Kashmiri politician, seen everywhere all the time. He has what the Kashmiris call ‘LACHAK’- the flexibility and charm that is important to conducting politics.

“Omar, on the other hand, presents a picture of contrasts: 100 per cent Indian, but only 50 per cent Kashmiri, and 50 per cent still the head boy of Sonawar School. Apart from his youth and freshness, he is straighter, he is correct and honest, a trait that has not always gone down well in his state.”

The author also does not elaborate on the strike by state government that received support from the National Conference leaders. Farooq, too, was against taking a tough stand and favored a settlement. The terrorists saw this as a moral victory.

Farooq’s leadership could also be unpredictable. He was known for shifting moods, emotional speeches, and political flexibility that sometimes looked like opportunism. Dulat acknowledges some of this, but never really holds Farooq accountable. Instead, he describes him as someone doing his best in a difficult environment- a figure who chose pragmatism over confrontation.

That’s where the book feels limited. It gives readers access to high-level conversations, informal interactions, and a close-up view of one political figure. But it doesn’t try to explain why things went wrong in Kashmir or how they might have gone differently. It’s more about remembering than reflecting, more about personal ties than public responsibility.

Readers looking for a detailed political analysis of Kashmir might be disappointed. But those who want to understand how personal relationships influence public history will find plenty to think about.

Regardless of Dulat’s evident admiration for Farooq, one cannot easily dismiss the acute understanding he brings to unraveling the persona of a man who remains a dominant force in Kashmir’s politics even today.

Dulat captures Farooq’s enduring relevance with striking clarity:

“The great man’s saga will not end in a whimper, because Farooq is not an ordinary man. Delhi cannot afford to give up on Farooq because without the singer, the song of Kashmir is not complete.”

The question that lingers in 2025 is: Who is the singer now-Farooq or his son, Omar?

(The Author works as Advisor with reputed Apeejay Education, New Delhi)