In a small room, he spends his days in silence. His world, once filled with vibrant colours, and intricate strokes has faded into monotony. Wide awake he stares at the ceiling of his small room in a sense his whole world. The brushes, the colour pots, and the drawing pads―his lifelong companions, with which he talked, slept and lived are no longer in his room. They all have been bundled up in a bag somewhere in a storeroom. The colourful world is now black and white.

Everything around him has changed. His creativity which was once at its peak and finding its expression in paintings, sculptures and teaching has almost ebbed now. It is no longer the colourful world in which he spent his six decades of life trying to save a vanishing art―Koshur Kalam: a unique form of miniature painting indigenous to Kashmir. His art, much like his physical strength, is slipping away.

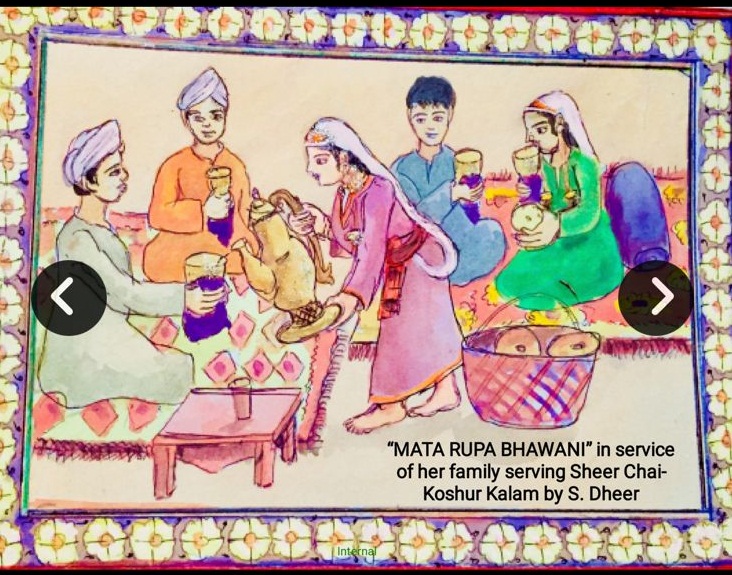

Pandit Shyam Lal Khar alias S. Dheer, the proponent of Koshur Kalam is the last surviving miniature artist and is no longer in a position to hold a brush in his hands to give pictorial imagination of his thoughts.

The art form which he pursued throughout his life with dedication and devotion is also dying a slow death. With nobody bothered to pass it on to posterity this art form is not appreciated by the art lovers nor the government is keen to preserve it. The artist who made it a mission to save the Koshur Kalam has never been appreciated by honouring any state award or financial support for his work. Despite his unwavering devotion, S. Dheer remains largely unrecognized, his sacrifices unnoticed, his name uncelebrated.

Born in 1937, S. Dheer’s artistic journey was unconventional. Though he pursued a Bachelors of Arts and later a B.Ed., his true calling lay elsewhere. A self-taught artist, he devoted his life to painting themes inspired by Trika philosophy and Shaivism, blending spirituality with artistic mastery. Unlike other artists who sought fame beyond their homeland, Dheer remained rooted in Kashmir, dedicating his life to painting and teaching.

His studio, Jyoti Studio, based in Mattan, was once a sanctum of creativity, where the strokes of his brush breathed life into forgotten traditions. Today, it stands abandoned, its walls peeling, its canvases gathering dust. His family has relocated to Jammu, and with them, the echoes of his once-thriving artistic sanctuary have faded. What remains is a relic of an art form on the brink of extinction.

Koshur Kalam, an exquisite and rare miniature painting style, is distinct in its delicate detailing, intricate motifs, and the use of natural pigments derived from minerals and plants. However, as modernity advanced, traditional art forms like Koshur Kalam began to fade into obscurity, overshadowed by mass-produced art and digital media.

Sham Lal Khar ‘Dheer’ is perhaps its last true custodian. Recognising the urgent need to preserve this art, he took it upon himself to document its history and techniques. His book, Koshur Kalam, published by the Academy of Art, Culture, and Languages, remains a landmark work, tracing the evolution of Indian miniature painting and culminating in an in-depth study of Kashmir’s own contribution to this artistic tradition. The book serves as a crucial reference for art students and historians, a testament to a master’s lifelong effort to safeguard a disappearing legacy.

But books alone cannot sustain an art form. Realising this, S. Dheer founded the School of Activity Fund and Fine Arts (SAFFA), an institution dedicated to training young artists in the traditional techniques of Koshur Kalam. In his own words, written for a special issue of a cultural magazine:

“Presently I feel ashamed to express that this land of mine full with multicolor flowers, scenic beauties and so magnificently delightful in this seasonal changes, is now not able to own such a splendid and elegant art, almost overlooked in the mist of computer haze and materialistic rush, getting no support from the so called exponents of art and literature. I had but to make my mind to start my own private institution so that at least a number of youngsters could be motivated to realise the importance of this art and propagate indigenous arts or crafts, to make it a common man’s skill.

This institution named as School of Activity Fund and Fine Arts (SAFFA), is still in its infancy, is Kashmir Kalam, along with other forgotten traditional arts. This intention is not only to train a new generation of artists in the bygone technique and to provide the possible assistance in shaping their talent, in the most effective Indigenous way and to make them the first-rate artists of quality in the near future, but also to evolve a method of making indigenous raw materials for the purpose as well.”

His vision was clear―not just to teach the techniques of Koshur Kalam but to create a self-sustaining ecosystem where artists could produce their own pigments, craft their own brushes, and ensure that every element of their artwork remained true to its Indigenous roots. But in a world where tradition struggles against the relentless tide of modernity, his dream remained largely unrealized.

Apart from being a maestro of the miniature art form, Sham Lal Dheer was also a distinguished writer and poet. His literary contributions spanned multiple genres and languages, showcasing his versatility. He penned scripts for television serials broadcast on Doordarshan and authored several novels including ‘Chandravat’ in Kashmiri, ‘Gat Zoon ‘in both Kashmiri and Urdu, and ‘Ducheot’ in Kashmiri.

His talent extended to drama as well, with works such as ‘Arsh se FarshTak’ in Urdu and Hindi, ‘Mayank Amavasi’ in Sanskrit, and ‘Kashmir Ki Rania’ in Hindi. Dheer’s poetic endeavours included ‘Lash Ki Mout’ in Hindi and Urdu, ‘Sangarsh’ in Hindi, and ‘Parmanand’ in Hindi.

As a short story writer he published notable works like ‘Shashi Sarla’ in Hindi, ‘Kali Jo Na Khili’ in Urdu, ‘Shree dhar Joo’ in Hindi and Urdu. Beyond fiction and poetry, he also contributed to documentary writing, with titles such as ‘Chinar’ in English and Urdu, ‘Pyasa Paani’ in Hindi and Urdu and ‘Floral Guide of Kashmir’ in Kashmiri.

Not widely known, Dheer was also a passionate plantsman with extensive knowledge of botany, particularly in medicinal herbs and their uses. His deep understanding of plant life complemented his artistic and literary pursuits, making him a polymath whose contributions extended far beyond the realm of miniature paintings. Despite his monumental efforts, S. Dheer remained an unsung hero. He never sought personal fame―his only desire was to see Koshur Kalam survive beyond his lifetime.

Maharaj Santoshi, a long-time friend of Dheer, recalls their association:

“The first artist I knew in my life was Sham Lal Khar who lived near our house in Mattan. He worked as a drawing teacher in a government school and also taught science to the students. His room in his house was a treat to the eyes of the beholder as colourful portraits of men, women and youthful girls appeared to be staring at them. Over the years my association with him deepened and I found aesthetic pleasure in his company. He always believed in simple living and his humble nature endeared him to all. He would paint for anyone who asked for it and not even charged a pie, not even the cost of the material. His art was his labour of love that never exhausted him. The sad thing is that he never consciously thought of beyond and remained confined to his native place. Had he made his artistic presence known by way of displaying in art exhibitions like other fellow artists, he too would have carved a name for himself. But for that he himself is responsible.

The worst thing that happened to us in 1990 did not happen to him. He stayed back in Kashmir and continued to paint in his own way. One day he surprised us when he displayed his miniature paintings with the sole purpose of bridging the gap with the forgotten native art. His book Koshur Kalam published by the Academy of Art Culture and Languages is a historical text as it traces the history of art in India and focuses on Koshur Kalam in the remaining four chapters. This book is a reference material and will guide many aspirants, particularly art students.

Sham Lal Khar is a true artist in his own sense but the recognition of his art remained elusive. He remained always withdrawn and unambitious. Had he the necessary drive to exhibit his artistic creations, he would have had many opportunities to prove his merit and find a place for himself. Now in his late eighties, this artist of Kashmir still thinks about art and remembers the days when with brush and colours he created a world of his own.”

Yet, his humility and unwillingness to seek recognition worked against him. Unlike other artists who actively sought exhibitions and accolades, Dheer remained confined to his room and native land. His reluctance to promote himself meant that while his work was extraordinary, it never reached the platforms that could have ensured its survival. The other main factor that inhibited him for showcasing his paintings in an exhibition was the financial support to promote his exhibition.

For Dheer, art was not just a passion―it was his very existence. Inspiration struck him unexpectedly―at a wedding, during a casual conversation, in the middle of a quiet afternoon. And when it did, he did not wait for the perfect canvas. If all he had was the back of an invitation card, a napkin, or a scrap of newspaper, he would use it to capture his vision. His creativity was relentless, refusing to be confined by circumstance.

Even now, in his late eighties, his mind remains tethered to his art. Though his hands no longer have the strength to wield a brush, his thoughts are still filled with images—of the landscapes he once painted, of the figures he so meticulously detailed, of the strokes he perfected over a lifetime. He remembers the days when color was his language, when every stroke was a prayer, and when art was his bridge to the divine.

But as time passes, the fear lingers: What happens when he is gone? Who will keep Koshur Kalam alive? With no institutional backing and few students to carry forward his legacy, the future of this exquisite art form looks bleak.

- Dheer’s story is not just the story of one artist; it is the story of many forgotten artisans, the custodians of dying traditions, whose dedication and genius fade into oblivion without recognition or support. The loss of Koshur Kalam would not just be the loss of a painting style—it would be the erasure of centuries of Kashmiri heritage.

Perhaps it is not too late. Perhaps there is still hope that the art form can be revived, that young artists can be inspired to take up the brush where Dheer left off, and that cultural institutions can acknowledge and preserve his work.

If we do not, then one day, Koshur Kalam will exist only in books and forgotten memories—its last keeper lost to time.

(Author can be reached at: [email protected])