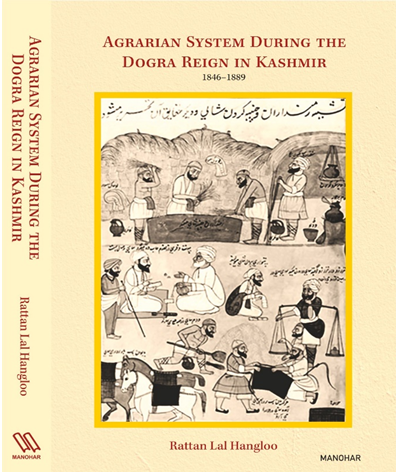

BOOK REVIEW

The book entitled ‘Agrarian System During Dogra Reign in Kashmir (1846-1889)’ by Professor Rattan Lal Hangloo, a world-renowned historian, is an important book that has attracted a large audience within the Kashmir valley and outside. Apart from a very insightful introduction and conclusion, the book deals with variety of important aspects of Kashmiris life such as; agricultural production, land revenue system, land revenue assignees and other grantees, condition of the peasantry and pattern of trade.

Kashmir awoke to a freezing dawn in 1846, when Kashmir was sold for seventy-five lakhs by British colonial masters to Gulab Singh, the unloyal lieutenant of Sikh army. Once he assumed the authority over the region the worst ever new terror griped the entire Kashmir. The dominant influence in newly established Dogra regime was exercised by the ‘revenue machinery’ that always found powerful justification for its tasks in the traditions of feudalism.

The author brilliantly illustrates how the functioning of the Dogra government as a whole, was ill-conceived, short sighted, unjust, and quite inconsistent with any desire to utilize the services of the regime for sensitive, intelligent and valuable Kashmiri peasants. Dogra Maharaja and his bureaucratic machinery had ready ideas about how best to subvert the welfare of public. The memory of Dogra raj still haunts Kashmir’s mind when we think how innocent Kashmiri folks were subjected to beggar (forced labour). Among other things, this aspect too, has received very serious attention by the author in this book.

This book is based on plethora of archival material, contemporary revenue records primary historical data, from dozens of repositories and empirical analysis of public opinion, surveys made by research organizations at different times. Author has utilized all the available sources more fully than many other scholars. Professor Rattan Lal Hangloo has viewed things from a deeper and purer level of intellectual sensitivity and has meticulously based every aspect on empirical reality.

The book describes the way Dogra Raj impacted our understanding of overall agrarian society and social relations. Starting from some concrete cases, this book has drawn a general framework for the theoretical cornerstones underlying the relationship between peasant and state in nineteenth century Kashmir. Author has shown clearly how the Dogra regime left majority of Kashmiris resource less despite their ceaseless efforts to maintain the burden of regime. Every minutest detail of the agricultural production, Land revenue machinery, the state demand, the chaotic condition of peasantry and trade in craft production that supplemented Kashmir’s economy, has been viewed from deeper and purer level of intellectualconsciousness.

It is an important source of reference for future researchers and as it expands our knowledge by offering a new perspective. Professor Rattan Lal Hangloo has made a brilliant contribution because Kashmir has very limited land for agriculture besides the region does not have multiple cropping pattern because of geographical limitations. In his enlightening and well-crafted book, the author has developed a newness for comprehending the intricacies that determined the conditions of peasantry despite their hard labour and in the process provided a perspective from which to view the crisis in Kashmir’s social life among the agrarian classes even today.

The author’s characterization of Dogra bureaucracy, its corruption, and the mechanism of fleecing the Kashmiri peasant is highly convincing and makes great deal of sense of his unique approach to study peasant societies. Every aspect, including Kashmir’s craft production and trade have been analyzed, with great originality, conceptual clarity, distinctive approach, sincerity of purpose and pious imagination. It was this unnaturally elaborate degradation that dragged cultured Kashmir’s life to its feet by the land-based aristocracy that occupied power and positions in Dogra Raj.

The moral authority enjoyed by the revenue administration during the height of Dogra rule was finally seriously undermined and frequently mocked by the same peasantry from late 19th century to end of Dogra Regime in 1947.

It is an interesting reflection of the author’s wide knowledge, experience and his perspective of looking at Kashmir’s rural society, economy, its complex challenges and responses passionately. The book is a brilliant contribution and insightful exploration of the way, the author has dealt with each aspect objectively.

I would like to gratefully acknowledge the service that Professor Rattan Lal Hangloo has rendered to Kashmiris by producing such a profound book with great intellectual honesty. As an intellectual Professor Rattan Lal Hangloo has always fearlessly taken upon himself the task to probe myths, interrogate institutional prerogatives, nature of state, politics and power.

(The is an Assistant Professor at the department of History, Maulana Azad National Urdu University, Hyderabad. Feedback: [email protected])