Kashmir’s legacy of exquisite handicrafts, known worldwide for their artistry, includes one of its most cherished treasures: the Pashmina shawl. Rooted in centuries of tradition, this luxurious textile reflects the region’s heritage and the enduring skill of its artisans.

Pashmina has a story as rich as its texture, tracing its origins to the Persian term “pashm,” meaning “wool.” In Kashmir, however, it refers to the fine, unspun wool sourced from the Changthangi goats of Ladakh. These prized animals, living at altitudes exceeding 13,500 feet, produce wool of unparalleled fineness, even thinner than human hair strands. The production process is as meticulous as it is remarkable, beginning in the hands of nomadic Changpa herders who shear the goats’ undercoats during the summer months. This rare wool is then transported to city markets, where skilled artisans transform it into delicate, handwoven Pashmina shawls, a symbol of luxury and heritage that has captivated royalty and laypeople alike.

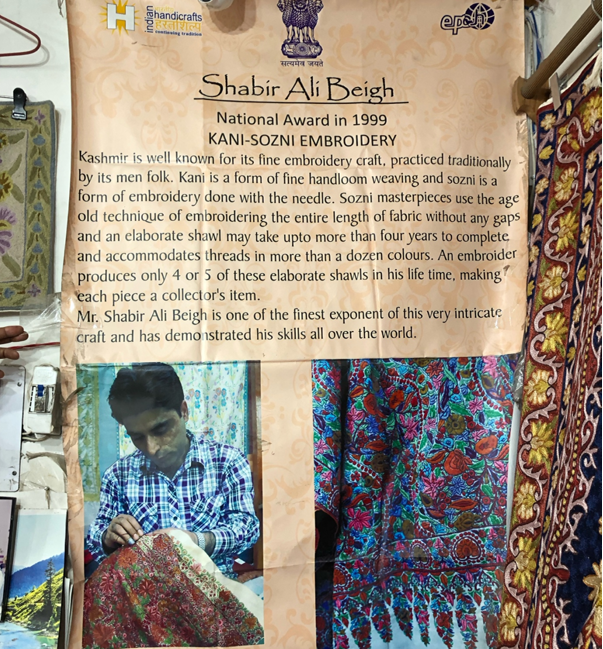

A Legacy in Srinagar: The Beigh Family’s Kashmir Sozni Atelier

At the heart of this tradition lies the Kashmir Sozni Atelier in Srinagar’s Alamgiri Bazar, run by the Beigh family, artisans who have honed their craft for over 200 years. The Beighs have garnered five national awards, including the esteemed Shilp Guru award, India’s highest honour in handicrafts. Sakib Ali Beigh, the atelier’s marketing manager, describes Pashmina production as a process likened to a “food chain,” where each stage—shearing, spinning, weaving, and embroidery—requires exceptional patience and skill.

Modernization and Its Discontents: The Challenges Facing Pashmina Artisans

While the demand for Pashmina remains strong, the art form faces serious threats. Mass-produced shawls, machine-made in mere minutes, have flooded the market, challenging the artistry of handwoven Pashmina, which traditionally took years to create. This shift is eroding the livelihoods of skilled artisans like the Beigh family. “The essence of our craft is being diluted by machines,” says Sakib, reflecting on the difficulties artisans face in sustaining this intricate art.

Compounding these challenges are economic pressures and limited government support. Although some financial aid is available, it falls short. Additionally, government-issued artisan registration cards, essential for accessing loans, grants, and opportunities to participate in exhibitions, are not being renewed consistently. For these artisans, the registration cards are vital in promoting their work and enabling economic stability.

External Pressures and a Call for Support

Beyond modernization, climate change is impacting the fragile ecosystem in which the Changthangi goats graze, threatening the wool supply itself. Rising costs of living, coupled with these environmental changes, are making it difficult for artisans to continue their craft. Aware of these mounting challenges, Sakib calls on the government and the public to support the artisans, both financially and through awareness initiatives that promote the uniqueness of handmade Pashmina.

A Future Rooted in Heritage and Innovation

Despite these challenges, there is a growing global movement toward sustainable and ethical fashion that could breathe new life into the Pashmina industry. By focusing on the handmade authenticity of Pashmina, artisans have the potential to reach new audiences who value craft over convenience. Organizations and government bodies are advocating for policies that protect these artisans and their rights, ensuring that their work can thrive in a modern marketplace.

As the world reawakens to the beauty of handmade artistry, the resilience of Kashmir’s Pashmina artisans stands as a testament to the enduring allure of tradition in a rapidly evolving world. Embracing both heritage and innovation, they continue to weave not just shawls but a story of cultural perseverance that speaks to generations.

(Author is a Freelancer. Feedback: @navyak07)