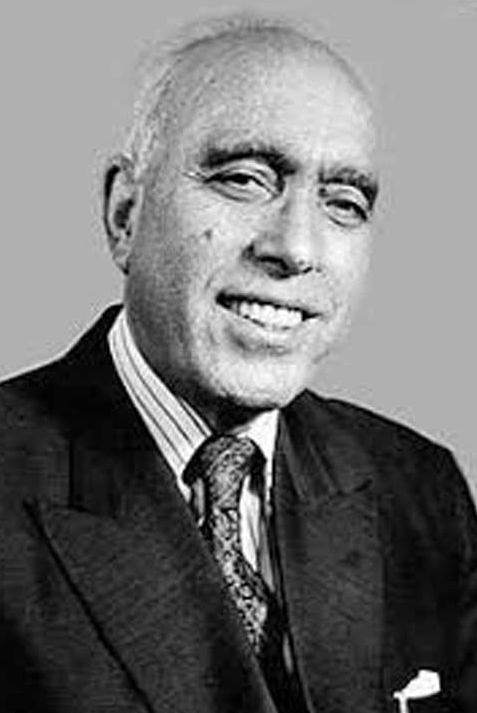

Cancelling holidays commemorating Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah’s birth and death anniversaries does not diminish his legacy. In fact, it highlights how deeply ingrained his contributions are in the fabric of our society. These holidays once served as a reminder of his significant role in shaping the political, social, and economic landscape of Jammu and Kashmir. Now, the fact of their cancellation, an attempted cancellation of the past, again serves to remind of his deep influence on the people of the region. His leadership, vision, and political philosophy continue to guide us, offering a framework for the future path the region should take.

Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah’s vision still inspires people to struggle for the dignity, autonomy, and justice. Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah has not been treated justly by history. Regardless of what critics may say, the reality is that he gave the people of Jammu and Kashmir what neither Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru nor Ali Mohammad Jinnah could provide to their respective people.

The 20th century was shaped by towering political figures, and Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah certainly stands one among them. History cannot afford to be unfair to him, for he led the people of Jammu and Kashmir out of abject poverty, transforming them from subjects into citizens. He spearheaded crucial social, political, and economic reforms that benefited the people of the state. To label him a “traitor” is baseless. What was “betrayal” from the standpoint of the entrenched landed elite of Jammu and Kashmir, was heroism from the perspective of its oppressed masses. In this case, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah may have been seen as a traitor by the ruling elites—both in Jammu and Kashmir and across the other parts of our country, as well as Pakistan. However, despite the distortion of official history, the people of Jammu and Kashmir continue to recognize his contributions.

Several important developments occurred during Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah’s lifetime, but these events have often been misrepresented to obscure the true historical struggle of the people of Jammu and Kashmir. These key moments include: A) the transformation of the Muslim Conference into the National Conference, B) the accession of Jammu and Kashmir to the Union of India, and C) the Indira-Sheikh Accord of 1975.

To better understand these developments, we need to examine them in their historical context and challenge the distortions that have been used to misrepresent the decisions Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah made, all of which were taken in the best interests of the people of Jammu and Kashmir.

The struggle for the rights of people of Jammu and Kashmir reached its peak in the 1930s, with the formation of the Muslim Conference under the leadership of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah. The movement’s primary aim was to put an end to the feudal exploitation of the Muslim population of Jammu and Kashmir, which was a significant issue at the time. As the struggle progressed, however, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah recognized that the problem of oppression and exploitation extended beyond just the Muslim community. It was not only Muslims who were suffering but also lower-caste Hindus, non-landed Dogras, Pandits, and Sikhs were facing similar injustices.

For the struggle to succeed, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah understood that it could not afford to exclude these marginalized groups. The fight for justice needed to be a collective, inclusive one. By the late 1930s, the movement had reached a crucial turning point. It was no longer enough to simply challenge the feudal system; the leadership needed to broaden its base. Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah realized that the name “Muslim Conference” was too narrow and exclusionary, and that the movement had to expand its scope to include all oppressed and exploited.

This led to the proposal to transform the Muslim Conference into the National Conference – a political party that would be open to people of all communities, whether Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, or otherwise. This reorientation was not just a strategic move but a necessary step to ensure that the struggle for freedom and justice could truly represent the aspirations of all the people of Jammu and Kashmir, regardless of their religious or ethnic background.

Even during his tenure as president of the Muslim Conference, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah had repeatedly expressed his opposition to communal politics, recognizing that such divisive ideologies would only harm the people of Jammu and Kashmir. He famously stated, “Communal politics doesn’t suit the people of Jammu and Kashmir. It can’t help us in removing the evils of poverty, hunger, illness, and above all, our slavery.”

By shifting to the National Conference, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah sought to ensure that the struggle for Jammu and Kashmir’s future was based on shared suffering and collective aspirations, rather than sectarian divides. This inclusive approach not only strengthened the movement but also paved the way for the creation of a united front against the oppressive forces of feudalism.

As World War II drew to a close, many colonies and semi-colonies were hopeful of gaining independence, and Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) was no exception. However, our struggle was not just for independence; it was primarily a fight against feudalism and for the rights of the people of Jammu and Kashmir.

At that time, the movements for the creation of two separate nation-states—India and Pakistan—were at their peak. While both nations came into being, J&K sought to remain independent. However, due to the strategic importance of its territory, both India and Pakistan sought to claim J&K as part of their dominions, which complicated matters for the region.

We must remember that the core of our struggle was against feudalism. If we base our understanding on this fundamental principle, we can conclude that the decision to accede to India was not just a pragmatic one, but the best option available at the time for the people of Jammu and Kashmir. It was Maharaja Hari Singh who decided to accede to union of India. Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah’s support for the accession came later, particularly in the context of the Poonch rebellion, which was later bolstered by Pakistan’s regular army. His decision was ultimately rooted in the same struggle for the rights of the people.

So, what choice did Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah have? Should he have supported Jinnah’s Pakistan, where land reforms were unlikely, or Nehru’s India, where the objectives of our struggle could be fulfilled? Some may argue that such reforms might have been possible in Pakistan as well, but the reality of the situation in the Pakistan-controlled parts of J&K tells a different story: there were no land reforms, abysmal education, and dreadful healthcare.

By supporting the accession to India, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah kept his promise to the people. He secured for them the most transformative change in their lives: land, which provided sustenance and livelihood for all. The land reforms brought economic mobility and laid the foundation for a better future. They opened doors for free and compulsory primary and higher education, as well as for affordable healthcare.

Can we say the same about the Pakistan-controlled parts of J&K? Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah got the best possible deal for the people he represented. History can no longer afford to be unjust to him for supporting the accession to the Union of India.

The Indra-Sheikh Accord should not be viewed as an act of betrayal but rather as a reflection of the intricate dynamics of power, necessity, and reconciliation. This accord was deeply influenced by the events surrounding the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971, Shimla Agreement 1972, which dramatically altered the political landscape of South Asia and, consequently, the situation in Jammu and Kashmir.

Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah’s long years in prison, combined with his observation of the shifting political climate, prompted a reevaluation of his stance. Over the decades, he had witnessed the gradual erosion of the state’s autonomy, as well as the growing influence of forces that sought to undermine the political framework that had been established in Jammu and Kashmir before his arrest in 1953. These forces included the rise of many fundamentalist groups which were supported by New Delhi and aimed at redirecting public discourse away from pressing issues like livelihood and survival towards a divisive narrative focused on identity and sectarian lines.

In this context, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, as a leader committed to the welfare of the people, felt compelled to reassess his position. His decision to pursue reconciliation was not a mere political maneuver but a strategic move to safeguard Jammu and Kashmir’s future. The accord was driven by two primary concerns: first, to prevent further erosion of the state’s special status, which was crucial to its distinct political identity; and second, to protect the people of Jammu and Kashmir from falling prey to the growing influence of communal forces that sought to exploit religious and sectarian divisions for political gain.

Ultimately, the Indira-Sheikh Accord can be seen as an attempt to navigate the delicate balance between autonomy, national unity, and the protection of the people’s interests. It reflected a pragmatic shift towards preserving the state’s unique status and defending it from the forces of extremism that threatened both its political integrity and the social fabric of its society. Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah’s vision centered on people’s welfare and secularism, not on serving the interests of a few or promoting communal divisions.

In today’s challenging times, we must look to our history and the struggle led by Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah. The movement was built on the sacrifices of our ancestors and represented the collective aspirations of the people. It was a vision that stood for all of us. In the ongoing battle to reclaim our rights and protect our land and identity, the legacy of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah and the people’s movement he championed are our most powerful weapons.

Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah was not just a leader for Kashmir; he was a champion for the landless masses, from Lakhanpur to Keran. His politics transcended religious and regional boundaries, advocating for the rights of all landless people. A secular leader, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah earned the ire of both Muslim and Hindu fundamentalists, who were driven by the interests of the landed class resisting land reforms.

Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah’s politics offers a model that can be adapted to our contemporary struggles. His legacy remains a beacon, not just in terms of his stature, but in building people’s movement and his ideals of governance rooted in the welfare of the people. Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah’s politics must inspire and guide both the development of a people’s movement and the governance that can confront the challenges we face today.

(Author is an activist associated with Jammu and Kashmir National Conference. Feedback: [email protected]))