The basic question which can be raised while dealing with the History of Science as a subject is that “why we should study the history of science?” The question could be best tackled by delving into the terms, why, study, history and science, piecemeal to fathom the real significance of the subject (History of Science) at hand. By a perusal of these terms we cannot only have glimpses of the ‘genesis’ of science and the development thereof, but can see its march throughout the history of human species. This awakening and awareness vis-à-vis science can redeem humanity of the harms of the ‘meaningless tussle’ caused by resorting to sticking to the racial or communal foundations of science as a discipline.

History, being a basic discipline, needs a serious perusal. Now, when it is prefixed to science, its significance multiplies manifold. This is because through history, humanity comes to know about its roots and by knowing the ‘story of science’ humans come to know about their progress, development and evolution as rational beings. As such, human beings are in a position to locate or position them-selves in the ‘time-space’ continuum! It can also bring home the fact that in the evolution of human society, science has never been absent or missing!

We know human beings have been created with moral sense, aesthetic sense and reason. Moral sense helps them decide the good and bad of thoughts, words, deeds and everything they come face to face with. Aesthetic sense makes them to decide between beauty and ugliness of both the theoretical (abstract) and practical (concrete) phenomena. It is the reason, however, which makes them to think about the whole existence.

The significance of this thinking process is so great that Aristotle defined the Absolute or the Supreme Being as: “Thought thinking Itself; and Its thinking is thinking on thinking!” It is this “obsession” of humans with “thought” that Rene Descartes had to declare: “Cogito, Ergo Sum; I think, therefore I am!” So, it is this thought which makes humans “curious” to “explore” things. It also motivates them to “seek explanations.” It leads to “critical thinking” and “acquisition of knowledge.” Such exercises finally lead to “problem-solving.” However, all these exercises begin with WHY?

Now, Cambridge Dictionary defines ‘study’ as ‘to learn about a subject.’ This ‘subject’ has multiple meanings. It could be an academic discipline, an idea or even a worldview. As such, ‘study’ would stand for ‘learning’ anything related to human society or the existence at large. In a ‘study,’ different aspects of the ‘subject’ concerned are minutely analyzed, reviewed, examined, investigated or simply researched. However, ‘study’ also includes ‘unlearning’ and ‘relearning’ besides ‘learning.’ Thus, in research, ‘study’ means to doubt and to make a critique of the established notions and opinions. As such, doubt, as a method of ‘study’ would lead to new findings which would consequently lead to conviction to a great degree.

We know ‘history’ deals with memory. Beginning with the memory of the individual’s interaction with herself/himself and with the nature around, this memory is a canvas of the memory of societies and states together. Now, this memory couldn’t become history (as a discipline) unless it is recorded and preserved. Naturally, this preservation takes place in the form of different records, which include folklore, hagiography, travelogues, and finally full-fledged books on history. Some have even counted ‘myths’ as a form of history. However, highest form of history is the established history. It is here that one’s (historian’s) hands are tied with evidence. Evidence, however, is not always absolute!

Etymologically, the term ‘science’ is derived from the Latin word ‘scientia,’ which means “knowledge” or “knowing!” Thus ‘science’ would stand for any knowledge which manifests some aspect of the ‘truth’ vis-à-vis different phenomena. However, technically ‘science’ means ‘the systematic study of the structure and behaviour of the physical and natural world through observation, experimentation, and the testing of theories against the evidence obtained.’

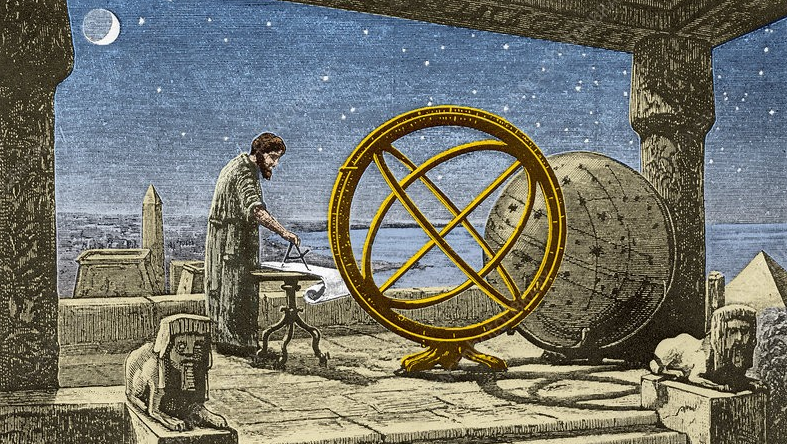

Humanity’s march on the path of science, however, has been humble and tedious. Take, for example, the case of alchemy which was a blend of natural philosophy, mysticism, and proto-science practiced in the Muslim World, China, Europe and India. It laid the groundwork for modern chemistry by fostering experimentation, developing chemical processes, and study of matter’s composition and properties. Relationship between astrology and astronomy, in spite of sharing a common origin and some terminology is, however, different. This is because astrology is still a ‘belief system’, while as astronomy is a ‘science!’

It is very interesting to note that humans have always loved ‘innovations!’ Every inquisitive mind has expressed uneasiness to imitate trodden paths blindly. Take, for example, the case of Aristotle, a philosopher (the First Teacher or the Reader) and a scientist, who exclaimed: “Plato is dear to us and truth is dear to us; but truth is dearer still!” This ‘quest for truth’ in the human instinct can seen (read) throughout the progress or evolution of science. For example:

- The Ptolemaic geocentricism was replaced by Copernican heliocentrism.

- Kepler removed the epicycles and replaced the circular orbits with elliptical ones.

- Hookes explained the elliptical path with centrifugal force.

- Newton, with his mathematical maneuver, made it still better.

- Laplace made the theory even better by explaining scientifically the stability of the solar system.

Likewise, Newton, Einstein, and Hawking represent a progression in our understanding of physics, with Newton laying the groundwork for classical mechanics, Einstein expanding that with relativity, and Hawking exploring the implications of quantum gravity and black holes.

History of Science would indeed help us to understand and acknowledge the cross-civilizational contributions to science and thus to humanity. The Journey/Story of Zero is a fascinating example toward this end. By the 6th century A. D., Aryabhatta and Brahmagupta had begun employing zero (emptiness, void, shunyata, so significant in Buddhism) in their calculations.

During the Islamic Golden Age (9th century), zero became fully integrated into mathematics through the Persian scholar, Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, the celebrated father of Algebra. The transmission of the zero from India to Europe through the Latin translation of al-Khwarizmi’s work in the 12th century manifested in the convergence of the mathematical wisdom of three civilizations. Perhaps these facts led Robert Briffault to deplore in his ‘The Making of Humanity’ that European Renaissance was delayed by 1,000 years because of the cumbersome nature of the Roman numerals.

As such, by pursuing History of Science, we can have an unbiased view of the share of different civilizations in science and technology. This can in turn lead to the understanding of the shared ethos of humanity. Humanity could thus have an opportunity to build a more humane ‘global society!’

(The Author is Sr. Assistant Professor, Higher Education Department, J&K. Feedback: [email protected])