- Quick Links

- About Us

- Contact Us

- E-Paper

Search

Archives

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

© 2022 Foxiz News Network. Ruby Design Company. All Rights Reserved.

Notification Show More

CM Omar Abdullah reaffirms social welfare as Government’s primary responsibility

Chief Minister Omar Abdullah reiterated the government’s firm commitment to welfare of all segments of society as Government’s main responsibility rather than an act of charity. Addressing a one-day event…

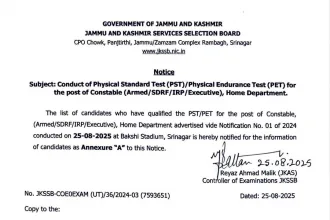

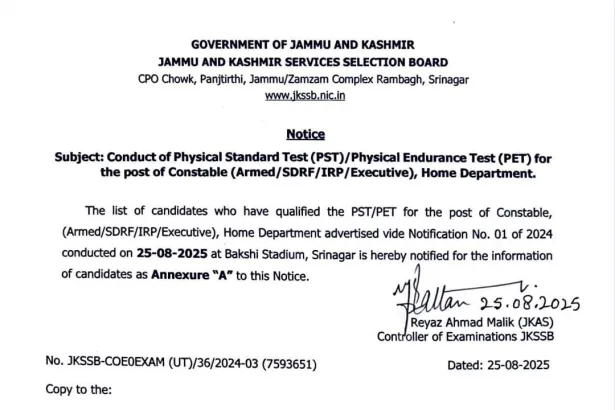

Result Declared for PET/PST for the Post of Constable held on 25 August 2025

The list of candidates who have qualified the PST/PET for the post of Constable, Home Department advertised vide Notification No. 01 of 2024 conducted on 25-08-2025 at Bakshi Stadium Srinagar…

No shortage of schemes, only awareness needed: Minister Itoo

‘Omar govt brought historic reforms but remote areas’ outreach remains challenge’

Div Com Garg reviews arrangements for visit of Parl committee on Home

Srinagar, Aug 25: Divisional Commissioner (Div Com) Kashmir, Anshul Garg on Monday…

Residents demand ENT, dermatologist for Kangan Sub-District Hospital

Kangan, Aug 25: Residents of Kangan in central Kashmir’s Ganderbal district have…

Ladakh: Pensi-la, Khardung La receive season’s first snowfall

Schools shut in Leh

DC Rajouri reviews Phase-II Data of 11th agri census

Rajouri, Aug 25: Deputy Commissioner Rajouri Abhishek Sharma on Monday chaired a…

J&K Bank organises financial inclusion and Re-KYC awareness camp in Samba, Jmu

Srinagar, Aug 25: Continuing its mission to promote financial inclusion across Jammu…

Induction prog for MBA, BBA freshers held at SMVDU

Jammu, Aug 25: The School of Business, Shri Mata Vaishno Devi University…

NCORD meeting : DC pitches for synchronised Intel Sharing to crack down on perpetrators of drug abuse

Reasi, Aug 25: A meeting of the District-Level Narco Coordination Committee (NCORD)…

Winged Symphony-2 : Asian Waterbird census 2025 records massive bird influx at Hokersar Wetland

The Hokersar Wetland Conservation Reserve, North India’s premier waterfowl habitat, has once again underscored its global ecological importance with a spectacular congregation of birds during this year’s winter season. The…

Heavy Rains in Jammu

Defence Minister Rajnath Singh visited the Government (GMC) Hospital in Jammu and inquired about the condition of the people who…

Sports

Centenary celebrations of Indian Chamber of Commerce : ICC’s immediate visit to Kashmir after Pahalgam tragedy sent strong message: Dr Jitendra

Says several reforms introduced in business & trade under Modi govt

Weather

14°C

Srinagar

clear sky

14° _ 14°

90%

1 km/h

Tue

25 °C

Wed

27 °C

Thu

28 °C

Fri

28 °C

Sat

21 °C